The Ruminant Liver & Photosensitisation

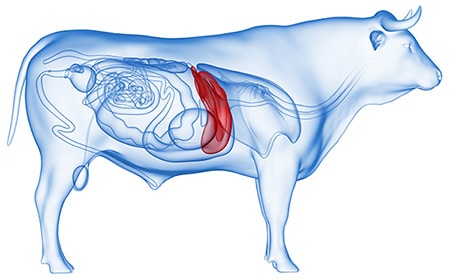

The ruminant liver has a number of imperative functions, including energy metabolism and the detoxification of fats, ammonia and other compounds. Animal nutrition and farm management practices can support liver function, and thus productivity and profitability.

Mycotoxins produced by fungi, and other toxins present in weeds, brassicas and pastures can reduce dry matter intake (DMI), rumen function and liver function. When liver damage occurs as a result of toxin ingestion, photosensitisation is commonly-observed as a secondary symptom. The visual presentation of facial eczema (FE) and other types of photosensitisation can be similar, but it is important to distinguish between the two, as the preventative tools differ. In-feed zinc oxide can assist with the prevention and management of FE, but it is unlikely to be an effective tool for other types of photosensitisation. A broad-spectrum toxin binder is the primary management tool for the majority of non-FE photosensitisation types.

What does the ruminant liver do?

The ruminant liver is the engine-room for various metabolic processes, most notably gluconeogenesis. Gluconeogenesis is the process by which glucogenic and ketogenic metabolites are synthesised to glucose in the liver. Volatile fatty acids (VFAs) produced by microbial fermentation in the rumen provide 60-80% of the energy required by ruminants; the remaining energy comes from fat, carbohydrate un-degraded in the rumen, and protein. Amino acids (protein) can also be used to synthesise glucose in the liver, but it is an energetically inefficient process.

Microbial fermentation of carbohydrates in the rumen produces the VFA propionate, which travels to the liver and is converted to glucose for the brain, mammary gland, foetus, muscles and other tissues. The liver is also a storage organ for glucose (as glycogen), as well as some vitamins and minerals.

The liver also detoxifies fats, ammonia and other compounds. Unused ammonia in the rumen is absorbed into the bloodstream, detoxified to urea in the liver, and recycled in saliva back to the rumen, or excreted in milk and urine.

The liver can also produce hormones important for fertility, as well as antibodies as a protective mechanism from disease.

Facial Eczema

Facial eczema (FE) is mainly observed in grazing cows in Gippsland when warm, humid weather between mid-summer and late-autumn provide conducive conditions for sporulation of the fungus Pithomyces chartarum. The spores of the fungus produce a mycotoxin called sporidesmin in the gastrointestinal tract, which is absorbed into the bloodstream and produces oxygen free radicals in the liver. This causes liver, bladder and mammary gland damage. Sporidesmin concentration in the bile ducts causes necrosis and inhibits bile secretion.

Chlorophyll is broken down in the rumen to phylloerythrin, a phototoxin which is normally absorbed into the blood and excreted in bile. However, if the bile ducts are blocked, circulating phylloerythrin reacts with ultraviolet (UV) light in the skin, causing photosensitisation. Blood serum levels of the enzyme gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) give the best indication of the severity of liver and bile duct damage (serum GGT >700 IU/L indicates severe damage).

Progression of the clinical symptoms of FE:

- Transient diarrhoea

- Reduced production

- Weight loss and reduced feed conversion efficiency (FCE)

- Reproductive issues

- Photosensitisation

- Restlessness, rubbing and shade seeking behaviours

- Lameness

- Skin lesions or sloughing

- Jaundice

- Death

Short-term use of zinc (usually zinc oxide for up to 100 days) at 20mg elemental zinc per kg live weight per day can provide protection against FE, and maintain protective serum zinc levels between 20-35 µmol/L. The zinc oxide should be 80% elemental zinc. Zinc supplementation should occur several weeks prior to pastures becoming toxic, which is often when there is a lot of dead leaf litter. The zinc helps to prevent cell damage and reduce the formation of oxygen free radicals by the toxin sporidesmin. The zinc can improve epithelial tissue health, but can also inhibit the intestinal absorption of copper. Long-term feeding of high doses of zinc can lead to toxicity, and can cause mineral deficiencies (such as copper) due to competitive exclusion; calcium absorption may also be affected. Long-term zinc feeding and toxicity can cause pancreatic fibrosis, affecting insulin secretion, thus animals may lose excessive weight.

Photosensitisation

Other forms of photosensitisation coloquially named “fire fever” or “swamp fever”, can occur as a result of liver damage. This photosensitisation can be caused by ingestion of rough dog’s tail, St John’s wort, capeweed, brassica or pastures with high fungal load. Brassicas including forage rape and turnips contain glucosinolates, which have been implicated in secondary photosensitisation. The high sulfur content in brassica crops can also reduce copper and selenium availability. Chlorophyll breakdown in ruminants produces phylloerythrin which may not be processed effectively by the liver if it is compromised by toxin damage. Circulating phototoxins in the blood may react with UV light in the skin resulting in sunburn, hair loss, swelling and blisters.

Prevention is always better than cure, as once the liver has been damaged, it takes time to repair. A toxin-binder may alleviate further liver damage, but only time will repair the pre-existing tissue damage. Even after animals recover from the visible signs of photosensitisation, permanent damage to the liver can have a lifelong impact on animal performance.

A toxin issue can be identified by one or multiple of the following:

- Reduced DMI

- Drop in milk production and/or live weight gain

- Reduced feed digestibility and FCE

- Fast rate of passage/scouring – bubbles, undigested crushed grain and fibre

- Panting – a toxin issue can make heat stress worse

- Irritation of the teats – kicking cups off

- Shaking/twitching of the head and ears

- Eye discharge and redness of the eyes

- Shade-seeking behaviour

- Animals huddling together (but there’s no flies)

- Swelling, inflammation and sloughing of the skin

- Lameness – standing in water

- Agitation

Treatment of clinical cases:

- Anti-inflammatory drugs

- Zinc suncream

- Reduce social and environmental stress

What nutritional strategies can Reids can help with?

- Assistance in identification of the underlying challenge.

- For facial eczema, short-term use of zinc oxide in the pellet/grain ration.

- For most other types of photosensitisation, use of a broad-spectrum toxin binder. Bentonite is a non-specific binder, but it can bind some NPN and toxins in the diet. It can also soothe the gastrointestinal tract.

- B Vitamins can reduce oxidative stress in the liver and reduce fat accumulation. B12 has a role in propionate conversion to glucose.

- Trace minerals to support the immune system.

- Betaine to assist with transport of lipids out of the liver. This creates more ideal conditions for gluconeogenesis and ureagenesis.

- Balanced diet in terms of the amount and type of protein and energy sources.

What other management strategies should producers consider?

- Avoid high-risk paddocks where possible, and try not to graze too close to the base of the sward where fungal load is likely to be high.

- Provide sufficient fibre in the diet.

- Dilute and complement the high risk cow feed with other forages, plus grain or pellets.

- Provide shade/shelter, especially during the hottest part of the day.

- Adequate water quality and availability.

- Manage body condition score. Excessive weight loss by ruminants means the liver will need to process and detoxify a lot more non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA).

- Underfed animals are more likely to graze harder, and eat things they should not such as weeds.

Summary

Fundamentally, ruminant nutrition is about optimising dry matter intake (DMI), rumen function and liver function. Anything we can do to support the liver and the digestive system will drive fertility, animal health and profitability outcomes.

Ruminants have adapted to handle base levels of dietary toxins. Protozoa, fungi and bacteria can help with a degree of detoxification in the rumen, but not managing toxin load appropriately can have a huge impact on the immune system and reproductive performance. When it comes to high risk feed sources, dilution is often the best solution.